Beskrivelse

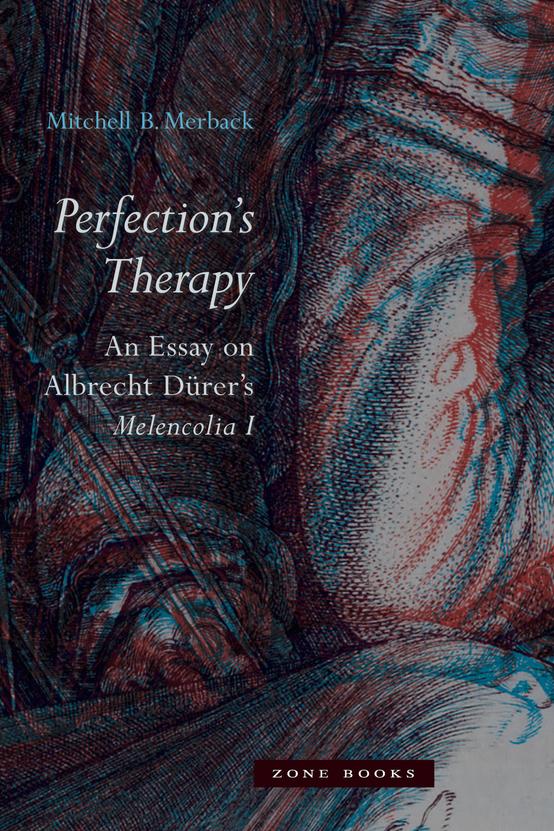

Albrecht Dürer’s master engraving, Melencolia I, has stood for centuries as a pictorial summa of knowledge about melancholia and an allegory of the limits of earthbound arts and sciences. Zealously interpreted since the nineteenth century, the work also presides over the origins of modern iconology. Yet more than a century of research has left us with a tangle of mutually contradictory theories.

In Perfection’s Therapy, Mitchell Merback discovers in Melencolia’s opacity a fascinating possibility: that Dürer’s masterpiece is not only an arresting diagnosis of melancholic distress, but an innovative instrument for its undoing. Merback deftly analyses the visual and narrative structure of Dürer’s image, revisits its philosophical and medical contexts, and resituates it within the long history of the therapeutic artifact. Placing Dürer’s project in dialogue with that of humanism’s founder, Francesco Petrarch, Merback also unearths the German artist’s ambition to act as a physician of the soul.

Celebrated by contemporaries as the “Apelles of our age,” and ever since as Germany’s first Renaissance painter-theorist, the Dürer we encounter here is also the first modern Christian artist, addressing himself to the distress of souls, including his own. Melencolia thus emerges as a key reference point in a project of spiritual-ethical therapy, a work designed to exercise the mind, rebalance the passions, remedy the soul, and help in getting on with the project of perfection.

“Reaching back through countless failed interpretations, Merback discerns the original function of art history’s most elusive print: to serve homeopathically as a balm for failed human endeavors. Wide-ranging and accessible, this book recovers the ethos and pathos of Dürer’s masterpiece while also opening a window to the troubled soul of Renaissance humanism.” — Joseph Leo Koerner, author of The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art and Bosch and Bruegel

“Merback is one of our era’s most ethically minded historians of art. In Perfection’s Therapy, he argues that the misery born of the pursuit of perfection, a sickness often associated with the modern genius, was an affliction that Dürer understood as a shared predicament. To show that Melencolia I served as an instrument for remedying this affliction, Merback convincingly reframes how the print mobilized cognitive processes. Like the early modern beholder Dürer’s art was designed to assist, we emerge from this intricate and persuasive argument having been moved to a new place in our thinking, more capable, and refreshed.” — Shira Brisman, author of Albrecht Dürer and the Epistolary Mode of Address