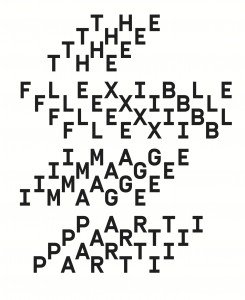

Objektiv # 13: The Flexible Image Part I

An editorial conversation between Objektiv’s board members Lucas Blalock, Ida Kierulf, Brian Sholis, Nina Strand and Susanne Østby Sæther.

Nina Strand, Editor-in-Chief: We have a working title for our issues in 2016, The Flexible Image. These issues will look at the current state of the (photographic) image, as it seems to expand into two distinct yet related manifestations: the image as text/sign versus the image as operation. Part one is about the image as operation: the image as touch, gesture and act. Whereas on the one hand, the image seems to work increasingly as a sign, emblematised by the emoji, on the other hand it is also increasingly being employed as a portal to various kinds of actions, typified by the on-screen icon. Thus the image can no longer be understood as an enclosed, representational entity that primarily addresses the faculty of vision. Rather, it works as an operating tool, addressing the full sensory capacity of the body, and touch in particular, thereby being entwined with the gesture. This is the kind of image that artist Harun Farocki has called “the operative image”: that is, “images that do not represent an object, but rather are part of an operation”.

For this issue we’re interviewing Ingrid Hoelzl, who’s just published Soft Image, Towards a new Theory of the Digital Image in collaboration with Rémi Marie. Throughout the book they show us how the image isn’t a fixed representational form, but is active and multi-platform: the soft image, the image as software. Hoelzl and Marie are currently blogging for Fotomuseum Winterthur’s blog Still Searching, a blog that seems to explore how to run a photo museum today. Its director, Duncan Forbes, stated in a previous interview I did with him that they are: “pursuing the expanded notion of the photographic and believe we’re at a sort of tipping point in the way the photographic is linked to the digital and the network.” Fotomuseum Winterthur want to pursue a programme that investigates this thoroughly. They have also launched an exhibition format called SITUATIONS, a multi-part programme that will respond to the rapid on-going developments in the photographic culture. I’d like to ask Brian, what are your thoughts on running a museum for photography today?

Brian Sholis, Curator of Photography, Cincinnati Art Museum: I’m intrigued by the Fotomuseum Winterthur’s recent programmes, and agree that photography museums would do well to respond to the medium’s rapidly changing technologies, uses and contexts. I write from the vantage point of an encyclopedic museum: the Cincinnati Art Museum collection encompasses 65,000 objects representing 6,000 years of human creation. What roles does photography, not even two centuries old, play in such an environment? In my opinion it should have a galvanising effect: a photography department should lead the way towards new exhibition and programme formats, new opportunities for visitor engagement and a recalibration of what a curator can (or should) do.

Platform-agnostic digital image files give photography curators one way to explore this. An image need not be a photographic print hung on a gallery wall, but instead could be converted into an outdoor mural, shared as part of an Instagram feed or e-mail newsletter, or offered to audience members for creative remixing. What’s the best presentation format for a given image? What’s the ideal way for a curator to share his or her ideas about the medium? Such questions can also be flipped. Across what networks should a curator look to find images and photographs worth exhibiting? Whose ideas about photography, other than a curator’s, can be creatively repurposed by the institution?

Relatedly, picture-taking today is often a self-reflexive and performative act. How might these characteristics be harnessed for new public programmes in and around the museum? In what ways can new programmes feed into exhibitions, thereby making them less static?

I’m a former editor newly embarked on a career as a curator. In what ways can the relationship between curating and editing be made more explicit? The discourse around photography is robust, and I’m eager to explore how the museum can harness and contribute to such conversations. I admire projects like Charlotte Cotton’s and Alex Klein’s Words Without Pictures, run through the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and later published as a book by Aperture, and online initiatives such as Winterthur’s Still Searching and the Walker Art Center’s homepage and online collections scholarship. Should museums embrace new-media platforms that they don’t control?

Each day at the museum inspires new questions about what’s possible with, through, and in photography. Finding the will to explore answers to them, and then the partners for that effort, is perhaps the biggest and most exciting challenge that photography curators face today.

I’d love to hear another museum perspective from Ida next.

Ida Kierulf, curator at Kunstnernes Hus: Photography – being in many ways the seminal visual medium of our time – saturates and informs all other contemporary art practices, and questions concerning what’s possible with, through, and in photography are always important in my work as a curator.

Curating photography throughout the years, it’s been important to explore the medium somehow from the inside, working with artists who use its inherent components in order to explore and expand it; this is where I find the most fruitful positions within photography today. Let me give some examples. The most beloved, and also debated, show I curated during my time as director of Fotogalleriet (The Photographer’s Gallery) in Oslo, was Sketches For The Meantime by the artists Stian Ådlandsvik and Lutz Rainer-Müller. Here the artists’ main gesture was to remove all the neon lighting from the gallery ceiling and turn it towards the outside of the gallery space, highlighting the immediate reality beyond the gallery walls. The darkened gallery space somehow became a camera body (camera lucida) or a paradoxical energy source for new images, and the gallery’s surroundings became scenes for latent drama. This exhibition also poetically and concretely manifested the dichotomy in photography between absence and presence, stillness and movement, light and dark.

Another artist I’ve exhibited here at Kunstnernes Hus who manages to explore the medium from within and bring to the table new insights into our perception and interpretation of images is Elad Lassry. Lassry wishes to create what he describes as “nervous pictures” – pictures that as he describes it “make your faculties fail, when your comfort about having visual information or knowing the world is somehow shaken”. He takes as his starting point images that are constantly circulated in our popular culture and are therefore somehow devoid of meaning, “orphaned images”, as he calls them. He then reworks them and strips them of any reference to their original content and context in order to make them appear as pure presence in front of the viewer. As our digital image culture has somehow become our greatest “reality thief”, I truly believe in artists who manage to demonstrate or challenge this numbing and deeply disturbing aspect of contemporary culture. Great art “is what makes life more interesting than art”, to quote Robert Filliou.

Turning to Lucas, whom I admire for his complex and poignant images, I’d simply like to ask how he understands the concept of what has now become the title of our double issue, namely The Flexible Image?

Lucas Blalock, photographer and writer: I want to expand the conversation around the image to also account for the picture or tableau, which is really the problem I spend most of my time wrestling with. In truth, I remain more interested in the photograph than I am in the image. For me, the photograph, with all of its baggage, makes for a particularly pertinent analogue to our experience of plugging into the various speeds of culture and economy that make up the contemporary world – always with some loss or caveat. The instability of the word “photograph” (versus the catchall of image with its connotations of total freedom) really helps this. We call a silver gelatin print, an inkjet print, a digital image, and a picture in a newspaper all “photographs”; much as we are “ourselves”, in different guises, in the networks that these various technologies and velocities represent. I’m interested in the dichotomy between the operational image and the sign that Nina brings up, but I also remain interested in the development of the photographic tableau in the way that it’s come about in the last 40 years of art making, and the possibilities of using the slower space of the picture (-hanging-on-the-wall) as a place to consider the mutations of the medium as well as the flexibilities being asked of us.

The word “flexible” brings to mind descriptions of the contemporary workforce, where this term can speak to a sense of freedom for some to travel across operations but also as an unending instability causing a great deal of anxiety and hardship for many others. Perhaps, these qualities of our communicable material are themselves a reflection of the condition of our current cultural format, or vice versa.

I do realise that this insistence on photography has an anachronistic quality, but continuing from this idea of the worker, one might say that the body itself could be posited as a kind of anachronism, except as a pusher of buttons – which, with next-generation interfaces, also seems sure to pass. I’m very interested in questions of the body and the virtual but mostly in terms of how one’s body can be implicated as central to the subject being addressed; the body’s status and inefficiency in high-speed flows; and the body as necessary to our understanding of a political subject.

This notion of interface perhaps leads us to Susanne, who I know is thinking about these things from another vantage. Could you speak about how you see all of this?

Susanne Østby Sæther, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Art History at the University of Oslo: Both in my scholarly and curatorial work I have for a number of years been guided by an interest in the relationship between contemporary art, media and technology. I’m specifically intrigued by art that takes stock of some of the effects that our living in a media-intensive environment has on the organisation of our senses and on the conditions of experience and agency. It seems to me that within the last few years the interface in general, and the haptic interface of touchscreens in particular, has become a central trope for exploring these concerns within much camera-based art. (This is also the topic of my essay that’s excerpted in this issue.) The influx of the haptic is for me especially evident in video art, for instance in work by film/video artists such as Trisha Baga, Camille Henrot, Helen Marten, James Richards, Susanne M. Winterling and Victoria Fu – typically present through a depiction of a hand that touches the screen and causes some kind of action – but I think it can also be traced in photography.

What I find so perceptively explored in many of these works is precisely their staging of the ambiguous role of the body in the face of the processes of digital, computational media. As you point out, Lucas, the human body is definitely inefficient or even incapable of perceiving the micro-scaled and high-speed flows and processes of computational media. This is where the interface comes in; it’s basically a translator between the human body and its senses and output on the one hand, and the data structures and data-flows of the computer on the other. Touchscreens and their haptic interfaces are thus a way of trying to bridge this split in the most efficient way, through engaging a sense that from our everyday life is associated with sensory certainty and immediacy. However, the sense of touch itself is in turn perhaps reorganised and destabilised, spilling this instability back in to other aspects of our everyday life.

I see the “flexible image” very much as part of this nexus, because it can be stretched between serving numerous purposes merely by being touched. Yet these touches have to be of a very particular kind, i.e. they have to be the highly formalised gestures patented by Apple etc., making gestures proprietary. Here I find that the notion of flexibility of the workforce and the precariousness enforced though the imperative to be flexible, which you bring up, Lucas, is definitely important, since it clearly draws out the imbrication between new media and a specific postindustrial organisation of labour, which is currently intensified through touch. Ultimately, then, we’re perhaps all engaged in a kind of “flexible” or precarious labour even when touching a flexible image to look at an Instagram feed or pay our bills...

PART I can be found all over Scandinavia and certain distributors world wide. PART II of The Flexible Image will be out in September 2016.

- Forlag: Objektiv

- Utgivelsesår: 2016

- Tidsskrift: Objektiv

- Kategori: Tidsskrifter

- Lagerstatus: Ikke på lagerVarsle meg når denne kommer på lager

- ISBN:

- Innbinding: Heftet